He is a rude, rough, foul-mouthed, clever troublemaker, who has concentrated his elemental magic on recovery. The Crow in Hughes’ poem is a trickster, with character elements taken from mythology, particularly Norse. The father, a Ted Hughes scholar, has chosen as his escort a figure taken from the Ted Hughes work Crow, which the poet described as his masterpiece. Crow does this both physically and mentally, sometime screaming their pain away, other times tricking them into accepting the necessity of their feelings.Īs a guide Crow is appropriate. He proceeds to forcefully thrust the family past its destruction. In essence the Crow is a earth-bound psychopomp, but instead of guiding the dead to hell he instead is guiding the psychologically damaged to to the sun-lit uplands of recovery. As he himself says, they ‘could learn a lot from me / That’s why I’m here.’.

An antropomorphised bird the father alone can see, Crow is determined to rescue the family through any means necessary.

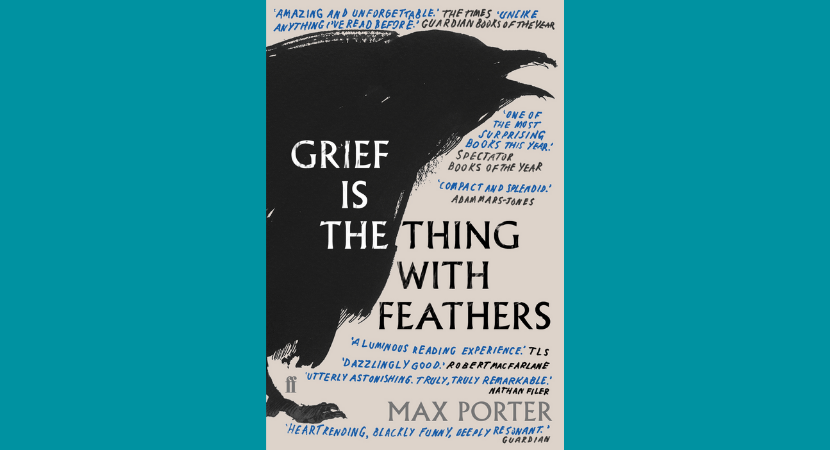

Each has their own voice, distinct from the start. Each of these three is a simple, but expertly drawn, summation of pain and anger and loss. Struggling to deal with their heartrending loss the trio are circling the drain, in danger of disappearing forever. The plot, such as it exists, centres on a recently widowed scholar and his two young sons. And it’s all of this within a slender 114 pages. Grief is in reality part-prose, part-poetry, part-academic text, part-abstract, freeform, memoir. For a start, the term novel fails to adequately describe the format, it’s just the best heuristic at hand. Grief is the thing with feathers by (shockingly) debut author Max Porter is just such a book.ĭescribing the novel is difficult. On occasion you come across a book that is so mesmeric, so delicate, intricate and beautiful that awe is the only appropriate response.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)